Standing at the prefecture window in Dijon, Paula and I realized with sudden, inescapable clarity that we were trapped in France.

On the surface, this was a situation unlikely to elicit sympathy from our friends. “Poor you, stuck in a beautiful country, in summer, with nothing but Paris and Aix-en-Provence and Normandy and your beautiful house in the Bourgogne countryside to keep you company. Boo-flippin’-hoo.”

We get it, really. It’s not hard to acknowledge that all of our problems are, almost by definition, #firstworldproblems.

But the truth is, we were heartbroken.

We were all set to leave for Canada at the end of the month, to visit our dear friend Debbie, and return to the high forests and lakes of cottage country east of the Georgian Bay. Debbie’s family home is in the heart of Algonquin country, on the shores of Ahmic Lake, about two hours north of Toronto. Three years ago, we had spent 10 magical days there; had broken bread with dear old friends, and made new ones.

And on our last night there, we sat in a boat, on a dead-calm lake, on a warm, clear night in late summer, and watched the Northern Lights dance across the sky for three unforgettable, life-changing hours.

That week was so overwhelming, so demonstrative of how beautiful and wondrous is this wide world, how many things there are yet to see, and people yet to meet, that it played a big part in our decision months later to go all-in and move to Europe. Ahmic holds an important place in our lives and hearts. And now, three years later, the band was getting back together. Everyone was coming back, and we were going to be there!

Then we weren’t. The French fonctionnaire behind the window in Dijon gave her little French shrug and blew her little French phfttt, to let us know that there was simply nothing to be done. It would be many weeks, she assured us with a little too much satisfaction, until something came in the mail granting us an appointment, and if we passed all the tests there, several more weeks until we got our little card that said we could stay in France another year.

By that time, our friends would be gone, the cabin closed for the winter, the Canadian nights already below freezing. And the money spent on our non-refundable tickets would dissolve like so many tears in the ocean.

And as Paula’s eyes filled, I realized bitterly that most of it was my fault. I should have known better.

The truth is that life in our stone house in our little French village is pretty spectacular, and the sense of gratitude and wonder that we express on our social media feeds isn’t exaggerated. Still, living in a foreign country isn’t all sunflowers and champagne.

By letting our long-stay visas expire, without our new ones in hand, I had placed us at the mercy of the French bureaucracy. Yes, there was a bad website translation over here, and a misleading word from an immigration officer over there. But it was all misdirection. In the end, I shouldn’t have let it happen. Not everything we read about France before we moved turned out to be true. But the stuff about an incomprehensibly dense, opaque, relentless and fearsome French bureaucracy – that was right on the money.

The good news is that, unlike in some of the more barbaric countries in the world, in France there are not bands of uniformed officers roaming around searching for people with expired visas, dragging them out of their cars and deporting them without due process. We were not under threat of deportation, at least not right away.

But leaving was a different matter. They weren’t going to kick us out. But if we left, they weren’t going to let us back in.

A lot of Americans aren’t clear about what the European Union means in its full implementation, but the important thing for purposes of living here is that (American) tourists are allowed to stay in the Eurozone for 90 days out of every 180 without a visa. That total is a rolling one, so the myths about being able to reset your automatic tourist visa by spending one day out of the Eurozone are just that – myths. And we are not tourists. When you live here, the consequences of being over the limit without a valid visa can be severe: If you leave, you can’t go home again.

We moved to France last August on a one-year long-stay visa that we obtained from the French Consulate in Houston, the office that oversees Louisiana. I won’t rehash the details of getting that visa (you can read about that here), but the process was extensive, and took many weeks of work to pull off.

And now we were face to face with the cold reality that the life we had built is dependent almost entirely upon the goodwill of a foreign government, subject to annual review. (We’re taking steps to change that, about which more later.)

We had submitted more than a dozen documents bearing varying degrees of certification and notarization to Houston for our first-year visa. And within three months of arriving in France, we had to report to the Office of Immigration and Integration (OFII) in Dijon with a whole other set of documents to receive our “Titre de sejour” – our residence permit.

What is the difference between the visa and the residence permit? I’ll be honest with you. After living here for a year, and after hours and hours of internet research, I still can not tell you. I know that because our visas were expiring, we needed to apply for renewal. And the renewal is for the “Titre de sejour.” Not for the visa. They’re different, but inextricably linked. Somehow.

Now here’s the part that will give you an idea of the full magnitude of the French fonctionnaire system: All of the documents we submitted to Houston last May, and all of the documents we submitted to OFII in Dijon last December – stacks and stacks of paper – were completely irrelevant to the renewal process.

In fact, neither the consulate nor OFII has anything to do with our renewal. Houston had decided that we could come to France. And OFII had decided we could stay for a year. But the prefecture in Dijon – basically the county government – would decide whether we got to stay any longer. And they weren’t even going to look at our previous files.

They have requirements of their own. Boy, do they have requirements.

Here’s just one example. Houston accepted a passport as adequate identification. So did OFII. But the prefecture wants a passport and a birth certificate. And not just the certificate. It should be accompanied by an apostille. WTF is that, you ask? You should look it up. It’s a document by one state agency that certifies that the document from the other state agency is in fact a document from that agency. We’d never heard of it before we moved to France. And now we’ve paid extra money to the states of Michigan and California for someone to say that the documents from Michigan and California actually came from Michigan and California. Go figure.

But wait! There’s more. We’re in France, and those pesky birth certificates and apostilles are in English. So they must be translated. And that translation can’t be done by your neighbor Didier, oh, no! The translations must be performed by a court-appointed translator with a court-approved translator’s license from the Dijon-approved list, charging court-appointed rates. Several days and $115 later, we had our certificates, our apostilles and our translations in hand.

And that was just one document.

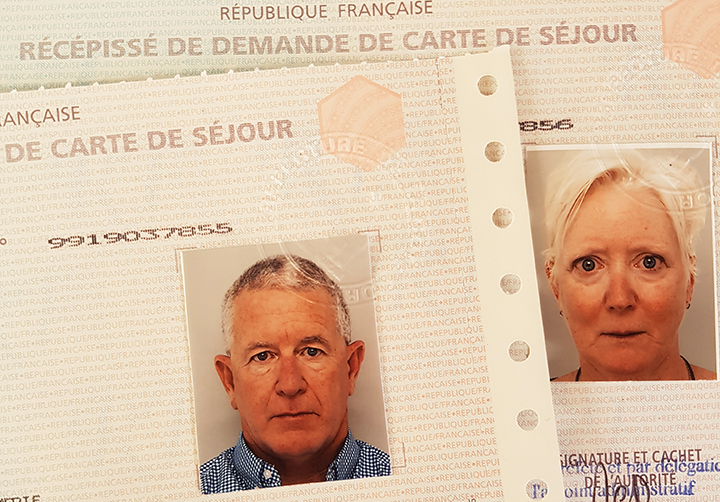

We applied for our visa renewals 16 days before they expired. It wasn’t nearly enough time, we learned. So we arrived at the prefecture on a Friday, three weeks later, to ask for a document called a récépissé. Basically, that says, “We have reviewed the file, it’s in good shape, and while we process and issue the new residence permit, you may let this fine person re-enter France with his expired visa.” Except the woman at the window was having none of it. Her position was basically: You filed late, you’ll have to wait.

Here’s the thing about France. All of the skills you learned in America are of no use here. If charm fails, yelling isn’t going to work. Outrage isn’t going to work. Demanding to see a supervisor isn’t going to work. These people have been in their jobs forever, and they’re not going anywhere. And there are only two possibilities: 1. They have the power to change your fate, but they have decided not to exercise it; or 2. They don’t have the power to change your fate, so you are just wasting your breath. And if it’s 1, you certainly don’t want to piss them off so much that you endanger your immigration status. And if it’s 2 . . . well, then, at that point you are the asshole, not them.

Maybe if we knew someone, it would be different. But we’ve been in the country only a year. We don’t know anybody in the prefecture, much less anybody with any power. So, after asking several times whether there was any possible solution, we had no choice but to take the woman’s word as final. We left the window and buried deep our disappointment.

And that’s when the miracle happened.

Our schedule for Dijon that day was: Go to the prefecture and get our permission slip; go to lunch; go to the Honda dealership and order our new car. We’ve researched cars for months, and the selection is very important to us. When you live in a place where Venice, Amsterdam, Barcelona, Brussels, Munich and Lucerne are all reasonably within a day’s drive (or maybe two short days), it’s important to have a comfortable car. This was going to be our world exploration machine.

We had our second meeting with Michel, our car salesman, set for 2 p.m. The truth was, neither of us felt much like lunch, but we marched grimly through some overcooked steak and a salad, then walked to the dealership. Michel speaks barely a word of English, so doing something as complicated as ordering a car takes our full attention. When he started asking us for name, address, phone number, email and the like, I was too exhausted to recite it in French, so I simply slid a piece of paper over to him that had all of our particulars written out.

I had written the details on the same page where I had typed a bullet-pointed list for the prefecture that described our situation, and the stakes. As Michel filled out our car order form, he read the bullet points. Then he asked us, “Are you having trouble with the prefecture?”

Yes, we explained. We had filed a little late, and now we would have to cancel a trip that meant a lot to us.

“My wife works at the prefecture,” Michel replied. “Maybe she could help.”

We thought he was joking. He wasn’t.

Four days later, we had an official appointment at 9:30 sharp, and we were back at the window in the prefecture in Dijon, as another woman helpfully processed our dossiers. Of course, there was one more glitch. When the machine scanned Paula’s récépissé, it rejected her passport photo because you couldn’t see her left ear. I’m not making this up.

So Paula sprinted across the lobby to get in line for the photo booth, terrified that it would stop this miracle that was happening in front of us. And I, stalling for time, told the woman at Window 11 that in fact, my wife did not have a left ear. She stopped and looked up from her screen with a look of horror on her face. “Vraiment?” she said. Really? I waited a beat, then said, “No, that’s not true.” I figured I’d either get a laugh, or a deportation order. Fortunately, she laughed.

Paula finally got her picture, and you can see at the top what it looks like when a slightly panicked American woman who is nearly blind without her glasses on but needs to make sure both of her ears are showing takes a picture of herself. A few moments later, the woman at the window handed us two very official looking récépissés, and told us to enjoy our trip.

In four to six weeks, we should get a text message telling us to come to the prefecture to pick up our new residence cards, good for one more year in France. I was tempted to take the récépissé two windows down and slam it against the window, Will Hunting style, and say to the woman who was so sure nothing could be done, “How do you like THEM apples?” But I realized that was the American thing to do.

Still, the whole experience has me thinking hard about changing our status. I learned recently that I have the right to an Irish passport, because my grandfather was born in Ireland. I’ve started that process in earnest.

An Irish passport would make me a citizen of the EU, and my wife the spouse of an EU citizen. It would transform our immigration status, and make the annual visa exercise moot. Of course, it’s a process that requires multiple documents and certifications and details. But it’s all in English.

What is also true is this: A week from today, we fly to Canada. And maybe – just maybe – we’ll look up one night, and see the green waves boiling up from the northern horizon, and we’ll be reminded once again that we live in a beautiful, beautiful world.

What a crazy system you are dealing with! Thanks for the beautiful words about our house on Ahmic. After just spending two weeks there I can’t wait to share it with you next week!

James and Paula,

Reading this brought Bob and me back through time to drinking champagne (or was it wine? or was it scotch/) with both of you in your beautiful home in your beautiful village and talking about your upcoming trip to Dijon to take care of this pesky paperwork.

Thank you for telling the story so powerfully that we felt that we were there with you at the prefecture’s window, struggling for the right words (in English or en francais) to get the recepisses! I am sure that every time you get into your new car, you will think about your ultimate success. (I am also sure that you didn’t negotiate too hard on the price of the voiture!)